The

Loss of the USS Memphis on 29 August 1916 - Was a Tsunami Responsible?

Analysis

of a Naval Disaster

George Pararas-Carayannis

(©)

Copyright 1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved

/ Information on this site is for viewing and personal information

protected by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction

of material from this site without written permission is prohibited.

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION

On August 29, 1916,

while anchored off Santo Domingo (Ciudad Trujillo) harbor in

the Dominican Republic, the armored cruiser U.S.S. Memphis was struck

broadside by numerous storm waves and, finally, by an enormous

wave which drove the ship into the rocks on the shore. The damage

to its hull and engines was irreparable. A subsequent

Court of Inquiry and the court-martial of the captain, attributed

the loss of the ship to a tsunami. The following analysis documents

that the loss of the ship was not due to a tsunami as the official

Navy records indicate and that it could have been prevented with

proper planning and vigilance. Human errors and lack of knowledge

of a passing hurricane were primarily responsible for the loss

of the Memphis.

The USS

Memphis

The USS Memphis

was a large 14,500-ton displacement armored cruiser that had

been launched on 3 December 1904 and originally named "Tennessee".

Her armament included four ten-inch guns in twin turrets, sixteen

six-inch guns, and twenty-two three-inch guns. The ship had two

steam powered engines and was capable of reaching a speed of

23 knots.

The USS

Memphis' Mission

In 1916, an unstable

government and political unrest at San Domingo (now the Dominican

Republic) required the dispatch of U.S. Marines to protect U.S.

interests on this Caribbean nation on the island of Hispaniola.

The USS Memphis was ordered to sail to the harbor of Santo

Domingo, the capital, to support the U.S. Marines stationed there.

Captain Edward J. Beach, was the ship's commander. Also,

the Memphis was the flagship of Rear Admiral Charles

F. Pond, the ranking U.S. Navy Commander in the region.or peace-keeping

patrol off the rebellion-torn Dominican Republic arrived at Santo

Domingo harbor in early August 1929.

The Harbor of Santo

Domingo The Harbor of Santo

Domingo

In July 1916, the

Memphis got underway for the West Indies, arriving at

San Domingo on 23 July . the ship was anchored at about 55 ft.

depth close to the mouth of Ozama river and near the 1177-ton

U.S. gunboat "Castine". Anchorage on this southern

side of the island was poor, because of its exposure to storms

from the south and the southeast.

Weather

Conditions at Santo Domingo in August 1916 - Ship Preparations

This Caribbean island

of Hispaniola - shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic -

lies in the middle of the hurricane belt and is subject to severe

storms and hurricanes from June to October. Concerned that it

was hurricane season, Captain Beach proposed to keep four boilers

of the Memphis going at all times to enable the ship to

get out of the harbor quickly if a hurricane approached. However,

because of US. Navy economy measures, Admiral Pond advised Captain

Beach to keep only two of the ship's boilers going for auxiliary

machinery, but to keep the other four boilers ready in case of

emergency.

Around August 22,

the barometric pressure dropped significantly and the weather

begun to deteriorate. Fearing that a storm or a hurricane was

approaching, Captain Beach ordered the other four boilers of

the ship to be fired and all arrangements to be made to get underway.

The feared hurricane did not occur but the preparedness exercise

was useful in demonstrating that the required steam pressure

to power the ship's engines could be raised in about 40 minutes.

Chronology

of Events in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 leading to the Loss

of USS Memphis

Chronology

of Events in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 leading to the Loss

of USS Memphis

The following chronology of events

summarizes entries from the ship's log, from observations by

the crew and people on the shore, from findings of a Court of

Inquiry, and from testimony at the court martial of the ship's

captain, following the loss of the ship. The following chronology of events

summarizes entries from the ship's log, from observations by

the crew and people on the shore, from findings of a Court of

Inquiry, and from testimony at the court martial of the ship's

captain, following the loss of the ship.

Satellite photo of

the Santo Domingo coast where the USS Memphis perished.

29 August 1916 - The few days after 22 August

1916 were uneventful. Both the Memphis and Castine

were riding gently in smooth sea, anchored off Santo Domingo.

No storm warnings

had been received. However, in the early afternoon of

29 August, even though there was no wind, suddenly the

waves became significantly higher. Both the Memphis and

Castine begun to roll considerably at their anchorages.

Long period waves could be seen coming into the harbor from the

east and breaking on the rocks.

15.30 - Concerned about the increasing

wave activity, an order was issued to the engine room of the

Memphis to raise steam pressure. However, major difficulties

were reported from the engine and boiler rooms. Water spray was

entering through the ventilators on the ship's deck which had

not been properly secured. Some of the ventilators on the

deck were subsequently shut off, but a lot of water had already

entered the engine rooms, creating problems in raising steam

pressure. The engine room reported to the bridge that there would

be adequate steam pressure from the four boilers to power the

engines by 16.35.

15.35 - 15.40 - In the next few minutes the swells

in the harbor increased considerably. The Memphis was

rolling very heavily and seas were now covering her decks. Spray

continued to come down the ventilator funnels. According

to officers on the bridge, the waves were so enormous that the

ship's keel bumped the seabed once or twice. Given the fact that

the ship was presumably anchored in 55 feet of water, this

meant that the waves must have been about 40 feet in height.

16.00 - Huge breakers capsized a motor

launch returning to the Memphis. There was nothing that

could be done to help the crew and passengers struggling in the

water. By that time, the gunboat Castine had managed

to increase steam pressure, start its engines and raise her anchor.

In an effort to rescue those in the water, the gunboat came into

the surf. However, the seas were too rough to lower a boat

and the Castine got dangerously close to the rocks. Fearing

that Castine may end up on the rocks, the rescue effort

was abandoned but life jackets were thrown in the water. Castine's

commander ordered to head out. The battered gunboat struggled

past the Memphis, but managed to get safely out to deeper

water.

16.30 - By that time the swell was even greater. The

Memphis kept on rolling 60 and perhaps as much as 70 degrees.

Her decks were being washed over by the waves and repeatedly

she was battered into the harbor bottom. 16.30 - By that time the swell was even greater. The

Memphis kept on rolling 60 and perhaps as much as 70 degrees.

Her decks were being washed over by the waves and repeatedly

she was battered into the harbor bottom.

With each wave, the

ship appeared to be lifting and dragging towards the rocks on

the shore. Captain Beach ordered the drop of a second anchor,

but the order was canceled when the engine room informed him

that steam pressure would be adequate in five minutes to start

the engines. With the ship rolling that much and the seas washing

over the decks, attempting to drop the second anchor was impossible.

16.35 - An immense wave estimated to

be about 70 feet in height was seen approaching the harbor.

16.38 - The engine room could not

generate sufficient steam pressure for the engines. The ship's

anchor cable was straining and appeared that it would break.

With only 90 lb. of steam pressure, Captain Beach had no choice

and could not wait for more steam. In an effort to at least turn

the ship's bow into the approaching huge wave, he ordered the

starboard engine full astern and the port engine full ahead.

It was a futile effort. There was simply not sufficient steam

pressure to turn the ship ninety degrees and complete the maneuver.

16.40 - The enormous wave was quickly

approaching the Memphis. It could be seen churning sediments

of sand and mud from the sea bottom. It appeared that it would

hit the ship broadside - the most vulnerable position. The shallower

water depth had slowed the wave down a bit but its height had

increased. In front of it, a 300 ft long trough had formed. As

the wave got closer to the Memphis, its peak begun to break.

The top of the breaking crest was now about 30-40 feet above

on the ship's bridge. The wave form appeared to consist of three

distinct steps, each separated by a large plateau.

The huge wave broke

thunderously upon the Memphis, completely engulfing it.

Two seamen trying to release the second anchor were washed overboard.

The wave's impact injured members of the crew. Other crew members

were injured or killed by steam or by steam inhalation when the

ship boilers exploded. The ship did not capsize but recovered

to an upright position but hit bottom hard, which normally would

be about twenty-five feet below her keel. The battering caused

great damage on her hull.

16.45 - Slowly, dragging her anchor,

the Memphis struck the first rocks at about 16.45. As each succeeding

wave pounded her, she was forced a little further ashore until

her port side crushed against the rocks, which pierced this side

repeatedly. The Memphis was still rolling from side to side,

although now firmly aground.

17.00 - At about 17.00 the battered

ship was given one final push by the waves, thus moving her hard

aground on Santo Domingo's rocky coast in water depth ranging

from 12-19 feet and only 40 feet from the cliffy shoreline. Large

holes in the ship's hull could be seen by observers on the shore.

Securing the Wreck

of the Memphis Securing the Wreck

of the Memphis

Actions that followed

the grounding of the Memphis are not of direct relevance to the

evaluation of causes that caused this disaster and details are

omitted since they have been adequately documented in U.S. Navy

archives and the literature. It will suffice to say only that,

as soon as the Memphis had gone firmly aground, Captain Beach

ordered the crew to fully secure the ship with ropes to the shore.

This was accomplished with the assistance of U.S. Marines and

hundreds of Dominicans on the cliffy shore of the harbor. Then

the captain ordered the evacuation of the injured, followed by

the evacuation of 850 others. This was done in an orderly and

safe fashion, using hawsers on land and ropes.

Death Toll

and Injuries - Damage to the Ship

What had started as

a normal routine afternoon on board the USS Memphis on

29 August 1916, in a matter of about one hour, turned into a

disaster of major proportions. Forty three people lost their

lives that fateful afternoon. Twenty five crew members died when

the ship's motor launch capsized in huge breakers at about 14.00,

as it was attempting to return to the ship. Another eight members

of the crew were lost when three boats sent to sea sank or were

wrecked attempting to reach shore after dark. Ten more died either

by being washed overboard or from burns and steam inhalation

when the ship's boilers exploded. The total casualties,numbered

43 dead and 204 injured.

The ship itself sustained

irreparable damage. Though she appeared to be nearly normal in

appearance above the water, the USS Memphis was a total

loss. Her bottom was driven in, her hull structure was badly

distorted and her boilers had exploded. Her 23,000 horsepower

steam power plant had been destroyed. The Memphis, would never

sail again. Although her guns and other components were eventually

salvaged, her punctured and twisted hull remained an abandoned

wreck on the cliffs of Santo Domingo for 21 years - before being

dismantled by ship breakers.

Conclusions

of the Court of Inquiry as to What Caused the Loss of the Memphis

The loss of the Memphis

was followed by a Court of Inquiry and the court martial of Captain

Edward J. Beach, the ship's commander. The court

concluded that conditions had deteriorated very rapidly to save

the Memphis. Also, that the heavy rolling of the ship and

the flooding from the ventilator funnels was the reason that

steam pressure could not be raised in time to fire the engines

and head out to sea, as the gunboat Castine had barely

managed to do. Complications in the engine room were blamed for

the failure. The Court found that Captain Beach was guilty of

not keeping up sufficient steam to get underway at short notice

and of not properly securing the ship for heavy weather.

The huge waves that

engulfed and wrecked the Memphis and drowned the sailors were

attributed to a "tropical disturbance", a "seismic

storm", but also to a "tsunami" that originated

from a seismic event somewhere in the depths of the Atlantic

Ocean or Caribbean Sea.

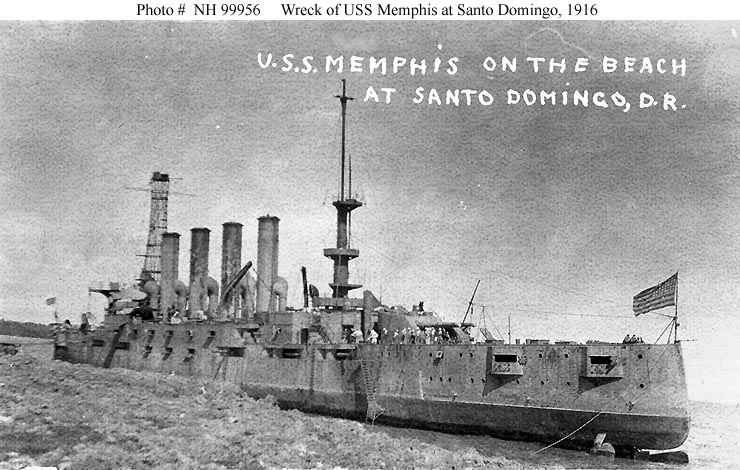

Photographs

of the USS Memphis Wreck taken in 1917 and Later

(U.S. Naval

Historical Center Photographs)

Analysis

of the Naval Disaster

Analysis

of the Naval Disaster

A Tsunami in the Caribbean

Sea was not Responsible for the Loss of USS Memphis A Tsunami in the Caribbean

Sea was not Responsible for the Loss of USS Memphis

The Navy's conclusion

that the loss of the Memphis was due to a 'seismic storm' or

a tsunami was erroneous. There is no such thing as a "seismic

storm". Furthermore, no tsunami occurred in late August

1916 in the Caribbean Sea or the Atlantic Ocean. The characteristics

of the waves observed breaking on the coastline of Santo Domingo

in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 were not those of a tsunami.

The Hurricanes of

1916 -Tracks of Hurricanes in 1916 in the Caribbean Sea and the

Western Atlantic Ocean

Tsunami waves were

not responsible for the loss of the Memphis. Most of the

historical tsunamis in the Caribbean region have been generated

by tectonic earthquakes. A review of historical catalogs of tsunamis

does not show an event specifically occurring on August 29, 1916.

The only earthquake and tsunami in the vicinity which could have

affected Santo Domingo occurred on April 24, 1916 north of Puerto

Rico, probably in the Mona Passage. Another earthquake/tsunami

occurred in the vicinity of Guatemala/Nicaragua on January 31,

1916. This event could not generate a tsunami at Santo Domingo.

A tsunami was generated on the Pacific side of Central America.

The waves that resulted in the loss of the USS Memphis

were not caused by a tsunami. There were no earthquakes of significance

in the region during the latter part of August 1916. Similarly

, there were no volcanic eruptions or major underwater landslides.

The Navy officers

who participated in the Court of Inquiry and the court martial

of the ship's captain did not appear to have much technical experience

or training about storm-generated waves or tsunamis. In 1916,

Oceanography and Meteorology had not developed sufficiently as

fields of science. Very little was known about tsunamis or the

modes of their generation. Also, it appears that very little

was known about tropical storms or hurricanes. There was no effective

way of tracking hurricanes or reporting vital weather data to

the Navy Command. Weather forecasting was at a rudimentary state

and there was no effective monitoring system or synoptic observations

which could be shared in real time. Finally, communications were

not very good in those days. Thus, it appears that the Navy Command

did not even have information on the three hurricanes that had

passed close to Santo Domingo in the month of August 1916. In

fact, on 18 August, one of these hurricanes had made landfall

at Corpus Christi, Texas, and had been responsible for widespread

destruction. Even if this information was known, it appears that

it was not conveyed to the captains of the Memphis or

the Castine at Santo Domingo.

The USS

Memphis was wrecked by storm waves generated by a passing hurricane

The location at Santo

Domingo where the Memphis and the Castine were anchored

was very vulnerable to approaching storm waves from the east

and southeast. The water depth of 55 feet where the Memphis had

dropped anchor was too shallow and within the breaking depth

zone of potential significant waves of longer period and wavelength,

generated by hurricanes.

As it will be demonstrated,

the series of huge breakers and the enormous wave that wrecked

the ship on the afternoon of 29 August 1916 were generated by

an approaching hurricane.

The most significant

of the waves that wrecked the Memphis were generated within this

hurricane's zone of maximum winds. Once outside the fetch region

of generation, these storm waves had outrun the slower moving

hurricane system and raced as swells across the Caribbean and

towards the harbor of Santo Domingo.

The following is an

account of the hurricanes that passed near the Dominican Republic

in August 1916 and an analysis of the storm waves of the particular

hurricane that caused the loss of the ship.

The Hurricanes of 1916 The Hurricanes of 1916

This region of the

Caribbean is in the middle of the hurricane belt and is subject

to severe tropical storms and hurricanes from June to October.

As shown by the hurricane tracking diagram, there were numerous

hurricanes that traversed the region in 1916. Most of them developed

in the Atlantic Ocean as tropical storms but when they reached

winds of more than 75 miles per hour, they were classified as

hurricanes. Three of these storm systems became hurricanes in

August 1916. Two of them crossed the Central Caribbean Sea, south

of Santo Domingo, and one headed north.

Track of the unnamed

1916 hurricane that struck Corpus Christi, Texas in 1916

The first of the unnamed

hurricanes in August 1916 (8/12 - 8/19) reached Category 3 and

made landfall at Corpus Christi, Texas - causing extensive destruction

there. The second unnamed hurricane (8/21 - 8/25) reached briefly

a Category 2 status as it passed near the island of Hispaniola,

but quickly degenerated into a tropical storm. Finally, the third

unnamed hurricane in late August (8/27 - 9/2) reached a Category

2 status with sustained winds of over 100 miles per hour. It

passed south of Santo Domingo on August 29. It is believed that

it was this hurricane that generated the huge waves at Santo

Domingo. Because its waves wrecked the USS Memphis, we

shall refer to it as "Hurricane Memphis".

The unnamed

Hurricane of August 12 - August 19, 1916

As the tracking indicates,

this hurricane reached Category 3 status passing south of Santo

Domingo on 14-15 of August. It continued in a northwest direction,

making landfall at Corpus Christi, Texas on August 18.

There is no information on any

unusual wave activity at Santo Domingo around August 14-15 when

this hurricane passed about 275 nautical miles to the south.

It appears that the directionality of the hurricane's path was

the reason that no significant waves struck the coast of Santo

Domingo. There is no information on any

unusual wave activity at Santo Domingo around August 14-15 when

this hurricane passed about 275 nautical miles to the south.

It appears that the directionality of the hurricane's path was

the reason that no significant waves struck the coast of Santo

Domingo.

However, this hurricane

was very destructive in the Corpus Christi, Texas region. In

fact it was the strongest storm since the Great Galveston storm

of 1900 had struck the area south of Corpus Christi

Although this hurricane

caused some damage, it moved very fast over the Texas coastal

area, thus resulting in low loss of life. Only 15 people died.

However, property damage was significant and was estimated at

$1,600,000 (1916 dollars). Most affected were the cities of Bishop,

Kingsville and Corpus Christi. In Corpus Christi, all the wharves

and most of the waterfront buildings were destroyed. There was

hardly any property that was not damaged. Most of the damage

resulted from the hurricane surge flooding and the superimposed

storm waves.

Evaluation

of Hurricane "Memphis" of 8/27 - 9/02, 1916

As the tracking diagram

indicates this particular system developed from a tropical storm

on 27 August to a Category 2 hurricane on 29 August. It reached

sustained winds of over 100 miles an hour and maximum probable

wind speeds and gusts of 125 miles per hour.

This was a dynamic

storm system which advanced into the Caribbean Basin rapidly.

The hurricane's speed of translation eastward is estimated at

about 15- 20 nautical miles per hour, since it traversed approximately

400 nautical miles on 29 August. At its closest point, the hurricane

center was about 250 nautical miles south of Santo Domingo.

The following is tracking

information for hurricane Memphis, followed by an analysis of

the storm waves it generated.

Tracking information

for Unnamed Hurricane (Hurricane Memphis) Passing South of Santo

Domingo on 29 August 1916 Tracking information

for Unnamed Hurricane (Hurricane Memphis) Passing South of Santo

Domingo on 29 August 1916

Time Lat

Lon Wind(mph) Pressure Storm type

------------------------------------------------------------------

6 GMT 8/27/16 14.0N

46.3W 70 -999 Tropical Storm

12 GMT 8/27/16 14.0N 48.5W 70 -999 Tropical Storm

18 GMT 8/27/16 14.3N 51.2W 75 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

0 GMT 8/28/16 14.7N 53.5W 75 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

6 GMT 8/28/16 15.1N 56.0W 80 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

12 GMT 8/28/16 15.3N 58.5W 85 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

18 GMT 8/28/16 15.4N 60.5W 85 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

0 GMT 8/29/16 15.5N

62.8W 90 989 Category 1 Hurricane

6 GMT 8/29/16 15.6N 65.1W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

12 GMT 8/29/16 15.6N 67.6W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

18 GMT 8/29/16 15.7N 69.2W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

0 GMT 8/30/16 15.9N 71.3W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

6 GMT 8/30/16 16.0N 73.1W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

12 GMT 8/30/16 16.2N 75.1W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

18 GMT 8/30/16 16.6N 76.7W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

0 GMT 8/31/16 16.8N 78.2W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

6 GMT 8/31/16 17.0N 79.6W 100 -999 Category 2 Hurricane

12 GMT 8/31/16 17.4N 81.0W 90 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

18 GMT 8/31/16 17.7N 82.0W 90 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

0 GMT 9/ 1/16 18.0N 83.2W 85 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

6 GMT 9/ 1/16 18.1N 84.1W 85 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

12 GMT 9/ 1/16 18.2N 85.3W 80 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

18 GMT 9/ 1/16 18.2N 86.4W 80 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

0 GMT 9/ 2/16 18.1N 87.6W 75 -999 Category 1 Hurricane

6 GMT 9/ 2/16 17.9N 89.3W 65 -999 Tropical Storm

12 GMT 9/ 2/16 17.0N 91.0W 35 -999 Tropical Depression

Hurricane

"Memphis" Wind Field - Directionality of Hurricane

Fetches, Duration and Significant Storm Waves and Swells

The hurricane's winds

blew in a counterclocwise pattern. Soon after the hurricane crossed

the Lesser Antilles islands arc, significant storm waves of longer

period begun developing within the radius of maximum winds, within

fetches of 10 to 20 nautical miles and over a durations of 1

to 2 hours.

As the hurricane progressed

westward in the Caribbean in the early morning hours of 29 August,

the fetches of maximum winds kept on changing direction in the

same counterclockwise pattern. Initially the winds generated

huge storm waves from an easterly direction. At the time, the

wave field in front and on either side of the hurricane center

consisted of locally generated seas and traveling swells from

other regions of the storm system. However, in the next few hours,

as the hurricane was approaching the longitude of Santo Domingo,

additional huge storm waves were generated, not only along the

east-west fetches of maximum winds, but along fetches with a

southeast - northwest orientation.

The longer period

storm waves begun to outrun the moving storm system and sorted

out as distinct wave trains traveling as swells towards the southern

coasts of the Dominican Republic. Because of the hurricane's

eastward movement and orientation of the fetches of maximum winds,

the waves that were generated became very directional towards

Santo Domingo. The direction of approach of converging swells

was from the east, from the east south-east, and from the south

east.

Estimate

of the Height and Period of the Most Significant Deep Water Storm

Wave Generated by Hurricane "Memphis" - The Killer

Wave

Based on limited data

for this historical hurricane but on certain known parameters

of other more recent hurricanes, mathematical modeling can be

applied to simulate the near sea surface wind field and to estimate

the upper limit of the long period waves generated by this storm

system. However, such modeling is a very involved process. For

the purpose of the present analysis, an empirical approach is

sufficient to roughly evaluate the Rayleigh wave distribution

function, and the upper limit of storm wave height variability,

as well as the maximum period, wavelength, and deep water height

of the most significant of the storm waves.

Based on this

analysis it can be concluded that it was this significan wave

or a very similar long period wave, which combined in resonance

with other storm waves, and resulted in the huge breaker that

engulfed the USS Memphis at 1640 on 29 August 1916 - wrecking

it on the rocks of Santo Domingo.

The significant height (Ho) and period

(To) of the most

significant wave generated in deep water at a point on the radius (R) of maximum wind of a hurricane can be calculated

mathematically, provided that the hurricane's pressure differential from the normal (Dp) is known, as well as the hurricane's

forward speed, its maximum gradient wind speed near the water

surface (30 feet above), and the Coriolis parameter (f) at that latitude. The mathematical equations

for this calculation are ommitted here but the results are presented.

Based on the limited

data available for this August 1916 hurricane ("Memphis"

- Category 2 hurricane), and assuming that its radius of maximum

winds was about 35 nautical miles away from the storm center

(a reasonable approximation for a hurricane of this type), the

forward speed was 20 knots, and the barometric pressure differential

of about 2.3 inches of mercury, the most significant deep water height (Ho) is calculated

to be about 58.9 feet.

The deep water period of this significant wave is

calculated to be about 16.1

seconds - indeed

a long period. Once outside the hurricane region this significant

wave maintained its wavelength and period, but attenuated somewhat

in height during its travel towards Santo Domingo.

Wave Transformation

in Shallow Water - Effects of Near Shore Refraction and Resonance

In the meantime, the

first of the longer period storm waves - which outrun the hurricane

system's eastward progression - begun arriving as swells at Santo

Domingo at about 1500 on August 29. Up to that time the sea had

been smooth and there were no reports of winds or a drop in barometric

pressure. At that time, the hurricane's center was fairly far

away at about 15.6 N and 67.6 W, approximately 300 nautical miles

southeast of Santo Domingo. However, these initial waves that

begun arriving at 1500 had been generated much earlier, mainly

from east-west fetches when the hurricane was as far as 600 nautical

miles away. The swells had traveled almost twice as fast as the

overall storm.

In the next hour,

additional storm waves generated closer to Santo Domingo - but

coming from a changing east-southeast direction - begun to outrun

the moving hurricane and interfere with swells arriving from

the east. The direction of the waves approaching Santo Domingo

kept on changing, but when the swells reached shallower water,

the bottom effects begun to be felt. Near-shore refraction unified

the waves' directional approach towards the harbor of Santo Domingo

and the location where the Memphis and the Castine were anchored.

Some of the waves that had similar periods and wavelengths arrived

in resonance, and begun to superimpose on each other - thus augmenting

their heights. The longer period waves begun to break in water

deeper than the 55 feet where presumably the Memphis was anchored.

These breaking waves, some striking broadside, washed over the

decks of the Memphis, and thus water went into the ventilator

shafts. This in turn caused the problems in raising steam for

the engines of the ship. The anchor was still holding, but probably

slightly dragging on the sea floor. Apparently not enough scope

had been let out on the anchor's chain. Dropping a second anchor

would not have helped the Memphis since not enough scope could

be released for the anchor to grab and be effective.

The Most Significant

of the Waves - According

to the crew on the Memphis, a huge wave appeared in the horizon

and its height was estimated to have been about 70 feet. This

must have been the most significant of the waves generated by

the hurricane which was estimated earlier to have a maximum deep

water height of 58.9 feet and a period of 16.1 seconds when it

left the fetch in the hurricane's region of maximum winds (estimated

to have been 125 knots/hour).

As this huge wave

got close to the Memphis, crew members observed that it had three

distinct steps and two plateaus on its forward face. Also, they

reported that its crest was preceded by a trough which was estimated

to be 300 ft. long. These observations suggest that this wave's

overall wavelength was about 600 feet and that two other waves

had superimposed on it when refraction begun to take place in

the shallows off Santo Domingo. Since the period of this extreme

wave was calculated to be 16.1 seconds in deep water (unchanged

by refraction), the deep water wave celerity (speed) can be estimated

- based on Airy and Cnoidal wave theories - to have been: C=L/T =600/16.1= 37.27 ft/sec (independent of depth). However

in water shallower than one half the wavelength (in this case

less than 300 feet) refraction by bathymetry and effects of resonance

begun to take place - thus combining this huge wave with two

other significant, long period waves approaching from different

sources and directions. This explains the three steps and plateaus

that were observed on the face of the huge wave.

The transformation

of the huge wave had begun about two minutes earlier. When the

wave reached water depths ranging much less than 1/2 its wavelength

(much less than 300 feet), the refraction effects became more

significant. Its speed was reduced considerably. The wave speed

was now dependent on the depth of the water and was governed

by the shallow water wave equation, which can be simplified as:

C = Square Root of

gxd - where d=depth of the water, and g= gravitational acceleration for that particular latitude. Based on solitary

wave theory, and without knowing the slope profile off Santo

Domingo harbor, an estimate of the breaker height can be made

based on the relationship between the breaker height (Hb) to the breaking

depth (Db). At the

breaker depth, all of the wave's potential energy became forward

kinetic energy - much to the detriment of Memphis. The relationship

from which the depth of the water where the wave will begin to

break can be obtained from Hb=Db/1.28. Since the observation was made

by members of the crew that the huge wave was about 30 to 40

feet above the bridge of the Memphis - and assuming that the

bridge was about 30 feet above sea level, the height of the wave

at breaking, Hb, must have been 70 feet. Thus

the huge wave must have begun breaking when it reached a depth

of 89.6 feet. Had the Memphis been anchored

in deeper water, like 120 feet instead of 55 feet, the entire

disaster would have been prevented. The ship would not have sustained

the earlier flooding of the engine room through the ventilators

by the earlier waves and it would have been able to raise steam

and sail to deeper water in a timely fashion. Alternatively,

if the Memphis had been anchored in 100 or better 120 feet of

water - instead of 55 feet - it would have been able to ride

all the swells, including the huge 70 foot wave, without a problem.

Unfortunately the

Memphis was anchored in too shallow and unsafe water depth. When

the huge wave had reached a depth of about 90 feet, its crest

peaked and the water particle velocity exceeded the wave's forward

velocity (celerity). At that breaking depth, all of the wave's

energy became kinetic and a huge volume of water begun to move

forward at a speed of 25-30 miles per hour. When this huge breaker

struck the Memphis broadside, it engulfed its decks and smokestacks

and pushed it onshore with tremendous force. At that point in

time, the Memphis was forever doomed. The anchor was of no use.

The engines, even if they had more than the 90 lbs of steam pressure,

would have not saved the ship. Even if the maneuver of turning

the ship's bow into the face of the wave had been completed,

it would have been futile within the breaking zone of this huge

wave. Neither the engine nor the anchor could have opposed the

huge wave force.

Human Errors

Contributed to the Loss of the USS Memphis

Human errors were

inadequately addressed by the Navy's Court of Inquiry into the

disaster and by the court martial of the ship's captain.

Complications in the engine room were blamed for the failure.

The Court found that the only human errors responsible for the

ship's loss was the captain's failure to keep sufficient steam

pressure to get underway at short notice and of not properly

securing the ship for heavy weather.

However, the Navy's

economy measures were the main reason that the boilers of the

Memphis were not fired at all times to keep steam pressure up

for the engines.

The huge waves that

wrecked the Memphis at the harbor of Santo Domingo in the afternoon

of 29 August 1916 were inacurrately attributed by the Court of

Inquiry to a "tropical disturbance", a "seismic

storm", but also to a "tsunami". The offiicial

Navy records still show that the loss of the Memphis was caused

by a tsunami or a tropical disturbance - but without further

explanation. As explained above, the waves that wrecked the Mempis

were not those of a tsunami but were generated by a hurricane

that passed south of Santo Domingo. What is perplexing is that

no one made a connection between this hurricane and the huge

waves it generated. It is apparent that storms were not properly

monitored in 1916 and that communications on weather information

were poor.

The loss of the Memphis

was a considerable disaster but, in fact, it was one that could

have been prevented with some rudimentary knowledge of storms,

storm waves, and with some additional preparation. The most serious

of the human errors that resulted in the loss of the ship was

the decision to drop anchor in only 55 feet of water. It was

an error in judgment, knowing very well that it was hurricqane

season. Anchoring in deeper water would have averted the disaster.

From the court martial proceedings, it appears that none of the

officers in charge had any training or conception of the speed

by which a storm would move, or that significant waves of greater

heights, wavelengths and periods could be generated by a distant

storm, or that the waves could outrun the storm and be immense

at distant locations. No one at that time recognized the potential

severity of such waves in shallow water, or realized that such

waves transform their potential energy into kinetic forward moving

energy once a certain depth is reached. Everyone was aware

that it was hurricane season, that the barometric pressure had

dropped previously and that there was a possibility of an approaching

hurricane and possible waves. They made preparations by

firing the engines on August 22nd and preparing for such an eventuality.

However, none considered the most simple and inexpensive solution

to this potential problem by simply anchoring the ship at 100-120

feet depth and out of harm's way. Lack of proper training on

weather and wave phenomena was the most important human error

in the loss of the USS Memphis.

Return to

Return to

Links to other

Pages

Links to other

Pages

Now available

from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other major bookstores. A signed

by the author copy can be also ordered by contacting directly

by email Aston

Forbes Press.

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

|